The Poison Train: East Palestine and the Derailment of Norfolk Southern 32N

A small American town struggles to survive after decades of bipartisan neglect cast a long shadow of uncertainty over its future.

I still hear the tall man say

To the children at their play

You’d better go home early

And you’d better stay away

Stay away from the line

Can’t you hear the railway humming

The grass has grown too tall

And the poison train is coming

—Michael O’Rourke, “The Poison Train”Pam Kline welcomed me through the front door of her home in East Palestine, Ohio, on a wet afternoon when we did not know if it was safe to be in the rain. About a week prior to our meeting, a train derailed in this small slice of the heartland, releasing toxic chemicals into the soil and sky. The house is a well-kept American Foursquare with an enclosed porch filled by the leathery smell of tobacco. She apologized for the odor as I entered the living room where her husband, Lenny, and a friendly Australian shepherd awaited. I told her the smell was pleasant. Even amid a crisis, the Klines were warm and kind.

But as we spoke, I could see the despair in their eyes. When Norfolk Southern train 32N careened off the tracks in the night on Feb. 3, it upended their lives and the lives of East Palestine’s roughly 5,000 residents.

Today, the flames that engulfed the train and its poisonous cargo have been extinguished. But there remains a sense of uncertainty and fear among the residents of East Palestine. They do not know who to trust. They are angry at the railroad company. And they feel neglected by their leaders.

Theirs is a story about a small American town struggling to survive after decades of bipartisan neglect cast a long shadow over their future.

East Palestine is blue-collar America. The median household income here is around $46,000, with a population that is more than 90 percent white and 99 percent U.S. citizens. It was founded as Mechanicsburg in 1828 but renamed in 1875 to accord with several other nearby Biblically-themed communities—New Galilee, Enon Valley, and so on—and thus reflect the religious sensibilities of the people.

It has always been a small but industrious village, manufacturing, among other things, electric wiring devices, automobile tires, and pottery. Indeed, the abundance of rich clay soils in the Upper Ohio River Valley helped make this region the pottery capital of America.

Both Pam and Lenny Kline work at E. R. Advanced Ceramics, which is home to century-old kilns. During World War II, the company devoted all of its operations to the war effort and covertly produced special refractories for the Manhattan Project.

Lenny said he has lived and worked in East Palestine all his life, only briefly leaving while serving in the military. The two even met at East Palestine High School. He wore a light blue Air Force hat that he occasionally removed and put back as we spoke.

They were not working on the night the train derailed, but, they said, their colleague was watching a kiln when it happened. He had just minutes to evacuate due to the plant’s close proximity to ground zero.

When I arrived at their home near East Palestine City Park, I noticed rows of blue metal E-Tank containers covered with thick black tarps sitting in the park, which was open to the public. “Safely store solids or sludges for disposal at your convenience,” the manufacturer’s website reads. Clean-up crews milled about as loud portable generators powered pumps running through nearby streams. When I tried to ask some workers about the containers and their contents, they politely declined to talk. The Klines said they had similar experiences.

“The people in this town feel the railroad’s controlling this whole situation,” Lenny said. “I’ll say that for East Palestine, from what I’ve seen and what I’ve heard,” he added firmly. Lenny removed his hat and leaned back in his chair and said that little about how the crisis was handled made sense.

It’s a sentiment shared by many townsfolk. But to really understand why it is pervasive, you have to revisit the scene of the crime.

Reconstructing a timeline of the events around the derailment is tricky, in part, because East Palestine does not have its own newspaper or media ecosystem. Newsgathering requires piecing reporting together from a myriad of outlets and scouring social media; local outlets, in particular, became indispensable.

I’ve done my best to produce an accurate sketch of what happened before and after what has been called one of the worst environmental disasters in recent American history.

The behemoth freight train originated from Madison, Illinois, hauling 151 cars, measuring 9,300 feet long, and weighing 18,000 tons. There were indications of trouble days before it derailed. On the evening of Feb. 1, it broke down at least once. Employees familiar with the matter said there were concerns from those working with the train about its massive size. They spoke to CBS News anonymously about the matter for fear of retaliation from Norfolk Southern.

“We shouldn’t be running trains that are 150 car lengths long,” one of them said. “There should be some limitations to the weight and the length of the trains. In this case, had the train not been 18,000 tons, it’s very likely the effects of the derailment would have been mitigated.” They also noted that every aspect of the operation is stretched to the limit. “The workers are exhausted, times for car inspections have been drastically cut, and there are no regulations on the size of these trains,” one said.

Two days after the breakdown, at 8:12 p.m. on Feb. 3, a camera at the Butech Bliss manufacturing facility in Salem, Ohio, captured sparks or flames flashing underneath the ill-fated train about 20 miles from where it would derail. The footage was obtained by The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which reported that a camera at a meat processing plant recorded the same glowing display one minute later.

The National Transportation Safety Board referenced the Butech Bliss video during a press conference along with another that evinced “preliminary indications of mechanical issues on one of the rail car axels.” The board noted that “the crew did receive an alarm from a wayside defect detector shortly before the derailment, indicating a mechanical issue. Then an emergency brake application initiated.”

The board published its initial findings about the crash on Feb. 23. It reported that the crew was not notified by an alarm about an axle issue until the train passed a sensor just east of East Palestine, not far from where it ultimately derailed. “This was 100 percent preventable,” Jennifer L. Homendy, the board’s chairwoman, said at a news conference in Washington. “We call things accidents; there is no accident. Every single event that we investigate is preventable.”

Shortly after it passed through Salem, the train derailed in East Palestine, near a Marathon Fuel gas station and behind a home heating oil supplier. A couple of teenagers leaving a high school basketball game saw an explosion while driving on Taggart Street and called the police. The clock was ticking, and the train, with its toxic cargo, was already burning.

Eleven of the cars that derailed carried hazardous chemicals. They included the following:

Butyl acrylate, a highly flammable liquid used for making paints.

Ethylhexyl acrylate, a combustible liquid that is used to make paint and plastics.

Ethylene glycol, a flammable liquid used in paint and antifreeze.

Vinyl chloride, a toxic and flammable chemical used to make polyvinyl chloride or PVC.

Vinyl chloride is also extremely carcinogenic.

But the residents of East Palestine could not have known that when they saw plumes of smoke climb into the night sky as flames licked the wreckage. Nor could the first responders who arrived on the scene.

Mayor Trent Conaway was at the crash site within minutes. “There were some small explosions, but it could be stuff in the boxcars. We’re not sure. As far as tankers, I don’t think any tankers blew up,” he told KDKA News. Smoke from the fiery wreck was so thick that it showed up on the weather radar of nearby news stations like a wicked storm.

A multi-state coalition from West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere in Ohio soon joined the first emergency crews to battle the inferno, who initially struggled amid temperatures so frigid that the trucks pumping water used by firefighters froze. “It’s a very big event,” Conaway told KDKA News. “Not many people have seen this in their history, in their careers as firefighters, so this is something they’re coming into that’s you know, you can train for it, but you really can’t train for something this big.”

On Feb. 4, Conaway issued an emergency declaration just before 9:30 a.m. as the cars continued to burn. About half the town’s residents were instructed to evacuate the area near the derailment site.

Conaway said during a press conference that even from his home on the edge of the village, there was a “horrible” smell in the air. Keith A. Drabick, East Palestine’s fire chief, said that day that air quality readings appeared normal but noted that authorities weren’t sure whether toxic materials had been exposed to the flames.

“If you have to come to East Palestine—don’t,” Drabick said. “Stay out of the area until we can get this mitigated.”

Initially, the plan was to let the train burn and clear the site after Norfolk Southern deemed it safe. But by Sunday night on Feb. 5, Gov. Mike DeWine urged hundreds of people who initially declined to evacuate within a one-mile radius of the crash site to leave immediately. “Within the last two hours, a drastic temperature change has taken place in a rail car, and there is now the potential of a catastrophic tanker failure which could cause an explosion with the potential of deadly shrapnel traveling up to a mile,” DeWine said in a statement.

Were that failure to occur, it would unleash hydrogen chloride and phosgene gas. Vinyl chloride breaks down into the former, a component of acid rain, when it is released into the atmosphere, and is converted into the latter, a highly toxic gas, with heat. Phosgene was used as a chemical weapon during World War I and claimed an estimated 85,000 lives. Five of the cars that derailed contained a combined 115,580 gallons of vinyl chloride.

DeWine added that those with children who refused to comply could be subject to arrest and deployed the Ohio National Guard that evening to assist local authorities. But the most controversial call came the following day.

On Feb. 6, DeWine announced that there would be a controlled release of the vinyl chloride that afternoon.

Following new modeling information conducted this morning by the Ohio National Guard and U.S. Department of Defense, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro are ordering an immediate evacuation in a one-mile by two-mile area surrounding East Palestine which includes parts of both Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The vinyl chloride contents of five rail cars are currently unstable and could potentially explode, causing deadly disbursement of shrapnel and toxic fumes. To alleviate the risk of uncontrollable shrapnel from an explosion, Norfolk Southern Railroad is planning a controlled release of the vinyl chloride at approximately 3:30 p.m. today.

According to Norfolk Southern Railroad, the controlled release process involves the burning of the rail cars’ chemicals, which will release fumes into the air that can be deadly if inhaled. Based on current weather patterns and the expected flow of the smoke and fumes, anyone who remains in the red affected area is facing grave danger of death. Anyone who remains in the yellow impacted area is at a high risk of severe injury, including skin burns and serious lung damage.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

It is believed that most individuals have already left the impacted areas, but law enforcement in both states are currently working to ensure that all individuals have left the vicinity prior to the controlled release. Depending on the exact amount of material currently inside the rail cars, the railroad estimates that the controlled release of chemicals could burn for 1 to 3 hours. It is unknown when residents will be able to return to their homes but an announcement will be made when it is safe to return.

East Palestine was thus faced with a catch-22: letting the tanks burn may well have released the hazardous chemical into the environment with a bang, but a controlled vent would accomplish the same thing with a whimper.

The proverbial die was cast. Emergency crews dug trenches around the cars into which the vinyl chloride was poured and ignited with flares, unleashing a toxic mass that mushroomed toward the sky from the pits. The thick, billowing black smoke poisoned every cloud it touched above and could be seen for miles below. It was as if this small town had opened a portal to some eldritch place.

During a press conference the day after the burn, Scott Deutsch of Norfolk-Southern boasted about the plan’s success. “Four of the cars have been cleared from the wreckage already,” he said. “We will continue to work our way down to get to the fifth car through all the damaged cars around it.” Deutsch added that the cars would be staged for inspection by the National Transportation Safety Board, after which they would be cut up and removed. The fires in the pits would be extinguished. State, federal, and civilian teams would monitor air and water quality. An Environmental Protection Agency and Norfolk Southern task force would visit residences and businesses to sample buildings and basements for real-time data. The 52nd Civil Support Team had onsite labs and monitoring systems around East Palestine.

Before people could reckon with the potential ramifications of the controlled burn, the mandatory evacuation order was lifted on the night of Feb. 8, when DeWine made the announcement in conjunction with the East Palestine Fire Department and the EPA. “All the readings we’ve been recording in the community have been normal concentrations, normal background, what you would find in almost any community operating outside,” James Justice of the EPA told reporters.

But not everyone was celebrating.

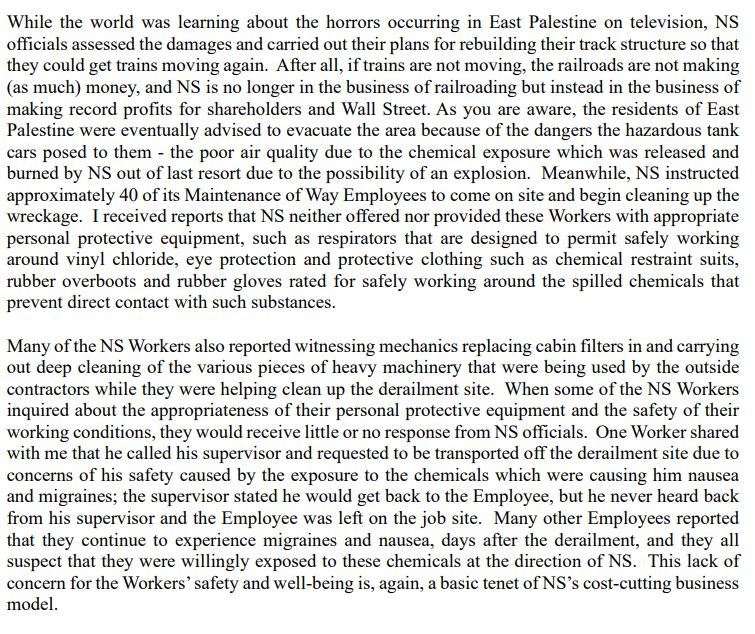

Jonathan Long, a union representative for the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees Division of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, provided more details about the cleanup in a scathing letter sent to DeWine on March 1. “I am writing to share with you the level of disregard that Norfolk Southern has for the safety of the railroad’s Workers, its track structure, and East Palestine and other American communities where NS operates,” he wrote. According to Long, workers involved in the operation were not given proper protective equipment and experienced migraines and nausea for days after the derailment.

Norfolk Southern challenged Long’s statement in a comment to The Hill, writing that workers were safe and properly equipped.

Locals, too, were unsettled by the operation and the speed with which it occurred. The air quality was fine after so many tons of toxic chemicals had been released—really? That didn’t sound right. They also complained that cleanup crews used vehicles that could spread contaminated or hazardous materials along East Palestine’s roads.

But what really infuriated them, including Conaway, was that Norfolk Southern trains started rolling on the line immediately after the evacuation order was lifted.

Conaway told reporters that Norfolk Southern had said operations wouldn’t resume until all residents returned to their houses. Instead, the railroad responsible for this disaster was back in business before the people of East Palestine could reopen their shops or get back into their homes. And for some residents, the trouble had only just begun.

Zsuzsa Gyenes had no idea a train hauling toxic chemicals derailed in East Palestine during the night. But she realized something was wrong when the fumes that filled her lungs made it hard to breathe and when her nine-year-old son, Maddik, with asthma began vomiting. They fled in the dark around 3 a.m. on Feb. 4 and awoke to a nightmare.

I met Gyenes outside an EPA press conference in East Palestine Park. When I tried to enter the building where it was held, a short, blonde woman with a green field jacket asked to see my nonexistent press credentials. I could see a crowd of reporters behind her. When I told her I had none to offer, she said I could watch the conference live on the agency’s website before repairing into the room and pulling the door shut behind her. I looked to my right. There sat Gyenes with a friend on a bench.

Like me, they did not know the meeting would be closed. Unlike me, they are locals. East Palestine is their home. Gyenes held a notepad and pen in her hands beneath a bellicose grin. She said that she had planned to grill the speakers.

Gyenes told me about her harrowing escape in the night from her home, about a mile away from where the train derailed, and how she’d been living in a hotel across the border in Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania. She spoke with a rapid cadence, explaining why she doesn’t believe anyone who has said East Palestine is perfectly safe, highlighting the incestuous relationship between corporations and regulatory agencies. She noted that the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health, a private firm contracted by Norfolk Southern to test water, soil, and air quality in East Palestine, has a history of serving corporate interests. The New York Times reported in 2010: “After a million gallons of oil spilled on a Louisiana town in 2005, after a flood of toxic coal ash smothered central Tennessee in 2008 and after defective Chinese drywall began plaguing Florida homeowners, the same firm was on the scene—saying everything was fine.”

The center also played a high-profile role for BP when it was hired after the Gulf of Mexico spill. BP relied on the firm’s monitoring to “prove” all was well when it wasn’t. The Times reported then:

As BP continues to claim that the leaking oil has caused “no significant exposures,” despite the hospitalization of several workers and the sparse release of test data, these observers of CTEH’s work say the firm has a vested interest in finding a clean bill of health to satisfy its corporate employer.

“It’s essentially the fox guarding the chicken coop,” said Nicholas Cheremisinoff, a former Exxon chemical engineer who now consults on pollution prevention.

“There is a huge incentive for them to under-report” the size of the spill, Cheremisinoff added, and "the same thing applies on the health and safety side.”

Another toxicologist familiar with CTEH, who requested anonymity to avoid retribution from the firm, described its chemical studies as designed to meet the goals of its clients. “They’re paid to say everything's OK,” this source said. “Their work product is, basically, they find the least protective rules and regulations and rely on those.”

Gyenes’s experiences with the firm have been eerily similar. After we met in the park, I followed up with her by phone to see how she and her son were doing since we first spoke.

Until Feb. 15, she said, Gyenes was being reimbursed for staying in a hotel with her son. But when reports about air and water safety returned clear, the housing help stopped. Gyenes said that after raising a little hell over the matter, she received a call from John Carden, a Norfolk Southern representative at the family assistance center in East Palestine. Surprised, Gyenes asked how he had obtained her number. “I pulled your file,” he replied, and proceeded to “lay it on thick,” Gyenes said, assuring her all would be fixed.

She was told to meet a testing team at her home. But 15 minutes before the appointed time, a toxicologist named Sarah Burnett with CTEH called her. “Sorry, we can’t get a team together because we need a police officer,” Burnett said, according to Gyenes. The former president had been in East Palestine, resulting in road closures and increased security. I asked her how she felt about Trump’s visit.

“I felt like he mostly did it for his own image. I mean, he has done a lot more than Biden has, absolutely,” she said. “He at least pretends like he cares; Biden acts like it’s not even f---ing happening,” she added. “But I don’t really feel like with Trump’s platform and his abilities—I don’t really think more bottled water and some paper towels is really going to help us. We shouldn’t even be f---ing cleaning this up ourselves.”

Our talk circled back to Burnett. Gyenes said she had a heated and confusing exchange with her over the phone. They discussed rescheduling the appointment before arguing over the health effects of the hazardous materials unleashed upon East Palestine. “She’s telling me she’s not heard of any symptoms, and I end up getting really frustrated with her,” Gyenes said. “I was just shocked when she said that to me.”

I reached out to Burnett for a comment. “We have not been made aware of symptoms in members of the community that are attributable to air quality in East Palestine,” she wrote by email. “Air monitoring data collected in the community indicates no short or long-term health risks concerning incident-related substances.”

People in and near East Palestine continue to report everything from persistent headaches to rashes that they attribute to the derailment.

The test was rescheduled for Feb. 23. But Gyenes said it was another no-show. When she attempted to contact Carden, Gyenes was told he had “stepped out.” So, she went down to the assistance center, where she met with Matt D’Elia, who also works with Norfolk Southern. But that only made things more confusing and frustrating for her. “He was given information by whoever was in charge there, he wouldn’t give me a name, wouldn’t let me talk to them—he said he was given orders by them to tell us that we were not getting any assistance,” Gyenes told me.

According to Gyenes, D’Elia told her: “You need to talk to an attorney to be able to talk to anybody.”

Attempts to contact D’Elia and Carden via phone, email, and in person at the assistance center for comment before publication were unsuccessful. Records show D’Elia and Carden are claim agents at Norfolk Southern. Part of the difficulty for people like Gyenes is that the railroad company rotates these agents in and out of East Palestine.

The shroud of uncertainty that has befallen East Palestine is made all the worse by this kind of confusion and miscommunication. And it has happened on every conceivable level. This is a small town where something big has happened, and the residents often feel in the dark. Who can they trust? Some, like Ohio Senator J.D. Vance, have tried to address the fears and anxieties of these people.

Vance spoke with the media outside Centenary United Methodist Church when I first visited East Palestine.

Vance has tried to stalk a middle road, not wanting to unduly frighten already worried locals while not taking reports giving the all-clear at face value from agencies and firms the public views with deep skepticism. During the press conference, he told locals they could take simple steps for the time being, like avoiding drinking tap water.

“I think that if I was living here, I would drink the bottled water for now,” he said. “Better safe than sorry, especially since it’s being provided for free. That’s the guidance I would give. And again, residents are going to make their own decisions on this, but my honest, personal advice is: I’d be drinking the bottled water right now.”

Later that day, the senator posted a video of himself at a creek in East Palestine dragging a stick across the rocky bed to surface a swirling chemical brew. The colorful toxic bands have been seen in other affected waters in and near the town, sometimes accompanied by the corpses of dead fish and other critters. As of this writing, more than 43,000 deaths of fish and other animals in Ohio have been attributed to the East Palestine incident.

But not everyone was happy with Vance’s rural romp. Texas Republican Congressman Troy Nehls, for example, attacked him for recommending bottled over tap water.

“The water within this municipality is safe to drink,” Nehls said. "They have a water treatment facility. As a matter of fact, I just went to a local restaurant here and I said, ‘put some tapwater [sic] in here,’ and I drank it. The water is safe to drink.”

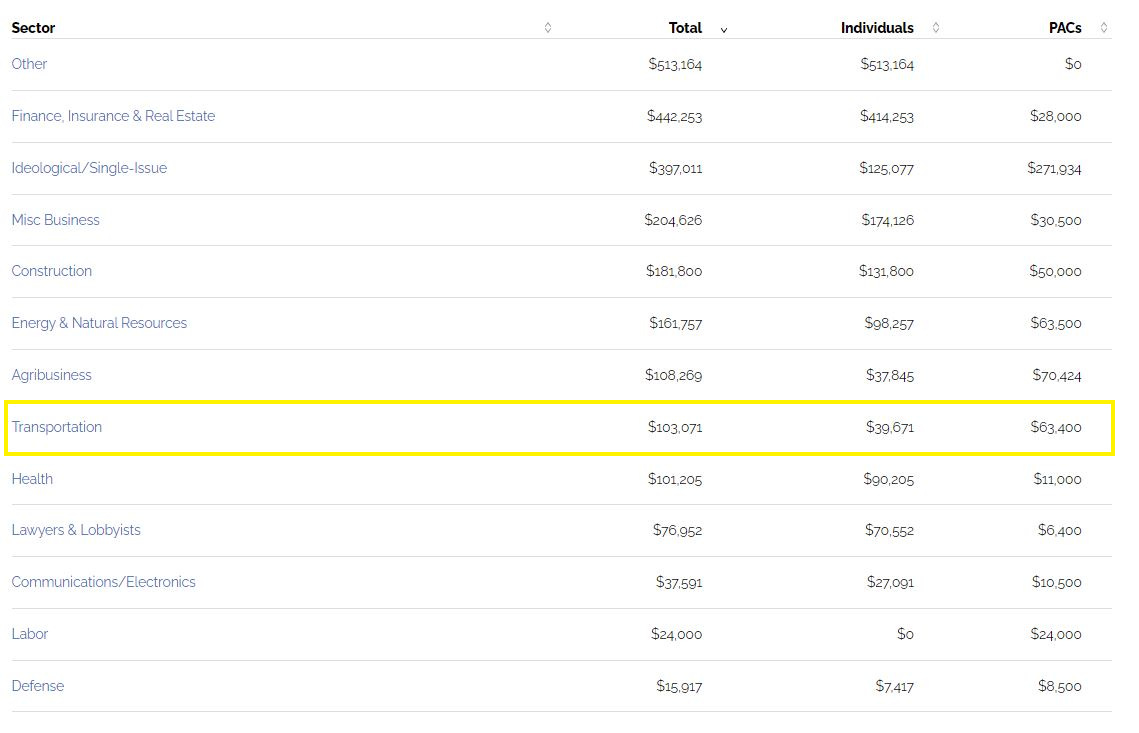

But Nehls has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from donors in the transportation sector, according to Open Secrets. That includes railroad companies.

Nehls has also received donations from Norfolk Southern.

A report of the railroad company’s contributions to candidates and political committees shows it gave to Nehls directly during the 2022 general election.

Things like this make the people of East Palestine distrust authority and doubt the independence of those involved in Norfolk Southern’s campaign to “make it right.” It certainly doesn’t help massage their anxieties that CTEH has reportedly asked homeowners to agree “to indemnify, release and hold harmless” the firm from “any and all legal claims, including for personal injury or property damage.” Some people interpreted that to mean those involved in the clean-up operation wouldn’t be liable if they said it was safe to return home when it wasn’t. When photos of the forms began to circulate, Norfolk Southern conducted damage control.

“Those incorrect forms were immediately pulled when the problem was discovered,” the railroad company said. “No one in the community has waived their legal rights against Norfolk Southern through this program or any interaction with us thus far.”

People don’t know what to believe. But they’re also not left with many options. Home values have already begun to fall in East Palestine and fewer customers are putting business owners, like Joy Mascher, in a pinch.

While walking through the village downtown, I noticed a sign on the sidewalk outside a shop called Flowers Straight from the Heart that asked passersby to pray for East Palestine. That was where I met Mascher, who has owned the business with her husband for nearly a decade. Like everyone else here, she is generous with her time and kind. But it’s easy to see on her face how this ordeal has affected her. There is a heaviness weighing on her shoulders.

She told me that she lives on the outskirts of town and keeps chickens. When the evacuation was declared, Mascher retreated there. But when she returned to the shop, the building was filled with a thick chemical smell. “My eyes and nose burned,” she said. “My son can sometimes still smell it.” The corners of her mouth turned down and she stared into the space across the room and placed her hand flat beneath her throat as if reliving the sensation.

Mascher has been left with only more questions. She doesn’t know if the help being offered will be enough. Norfolk Southern has asked business owners to provide three years of back paperwork to qualify for assistance. But some of them aren’t even comfortable fully reopening yet over safety concerns. Others I spoke with aren’t sure they’ll qualify for help.

Around town, people continue to report a chemical smell wafting into the air whenever a train rolls through the town, which might have something to do with how the site was managed after the wreck.

Most of the focus was on the controlled burn of hazardous chemicals, which gave rise to a photogenic black cloud. But the main concern now is Norfolk Southern’s handling of contaminated soil: burying it. A letter from the EPA to Norfolk Southern obtained by WKBN states:

Five rail car tankers of vinyl chloride were intentionally breached; the vinyl chloride was diverted to an excavated trench and then burned off. Areas of contaminated soil and free liquids were observed and potentially covered and/or filled during reconstruction of the rail line including portions of the trench /burn pit that was used for the open burn off of vinyl chloride.

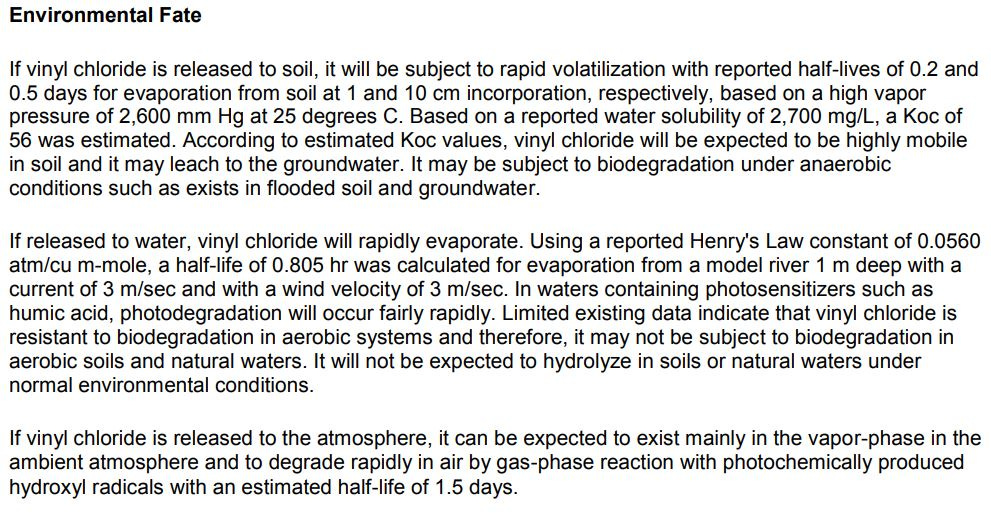

Reporters from WDTN consulted Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice on this matter. Rice has a Ph.D. in soil science and has been working for Bennett & Williams Environmental Consultants since 1986. She told WDTN that it is “possible vinyl chloride can travel through the ground as rain and precipitation move through the soil. It then has the potential to reach groundwater and eventually hit well fields.”

That’s no surprise, which is why Chris Kline told me he doesn’t understand why Norfolk Southern has managed things the way it has. He is the son of Pam and Lenny Kline, and he grew up in East Palestine and spent much of his life there. Today, he lives five miles away in New Waterford, where he is a councilman.

Kline works for Enviroscapes, an Ohio-based landscaping company that partners with public utilities, and he knows a thing or two about soil. Kline believes Norfolk Southern didn’t properly manage the site from the start. “It wasn’t remediated,” he said. “There was no removal of the contaminated soil. The tanks were pushed to the side, tracks were put in, and trains were running the day the evacuation order was lifted.”

“There’s multiple different types of soil remediation,” he added. “It’s basically the removal of anything that’s not supposed to be in that soil.”

He explained that there are different methods to achieve this. He reckoned the right thing would have been soil encapsulation, which entails isolating the contaminants to keep them from spreading by mixing the soil with cement, concrete, or lime. A fact sheet on the chemical published by the EPA states that “vinyl chloride will be expected to be highly mobile in soil and it may leach to the groundwater.”

Kline said he wasn’t sure if that would have been the best solution. But it would still be better than what Norfolk Southern did in essence: “covered it up and walked away.”

Norfolk Southern’s public responses to allegations that it failed to properly remediate the site have not inspired confidence. In its reply to WDTN, the railroad company wrote:

During the initial response work at the site, involving moving equipment, etc., some soil is moved around to best complete that initial phase. We will continue to remediate the site, including the removal of soil, to reach or exceed regulatory standards. Soil taken from the site is moved to a separate site for testing before being safely disposed of.

“Moved around” is not the same as completely removed. It also seems to skirt the real question: if Norfolk Southern has to rip up the tracks to remove contaminated soil, would it actually do that?

To make matters worse, the anger at the railroad company has assumed a personal dimension that spills over into the lives of others. Kline told me that he knows blue-collar Norfolk Southern workers who have been treated unfairly by people they know.

“I don’t hold anything against these boots-on-the-ground type guys who are just out there trying to work and provide for their families,” he said. “The little guy gets put into these tough situations by the suits who are sitting in their offices breathing clean air and drinking clean tap water.”

That is true. But who, then, is at fault for what happened here?

Norfolk Southern is, in many ways, the perfect villain. Its top shareholders are Vanguard Group and BlackRock, two gargantuan financial firms whose names seem to ooze avarice and who bring to mind Matt Taibbi’s characterization of Goldman Sachs: “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” Both Vanguard and BlackRock are part of the vampire Cephalopoda family.

The railroad company is also committed to the farce that is the environmental, social, and corporate governance framework. “At Norfolk Southern, success means operating safely and sustainably, empowering people, and innovating for the future while providing reliable service,” reads a message from president and CEO Alan H. Shaw in Norfolk Southern’s 2022 ESG report.

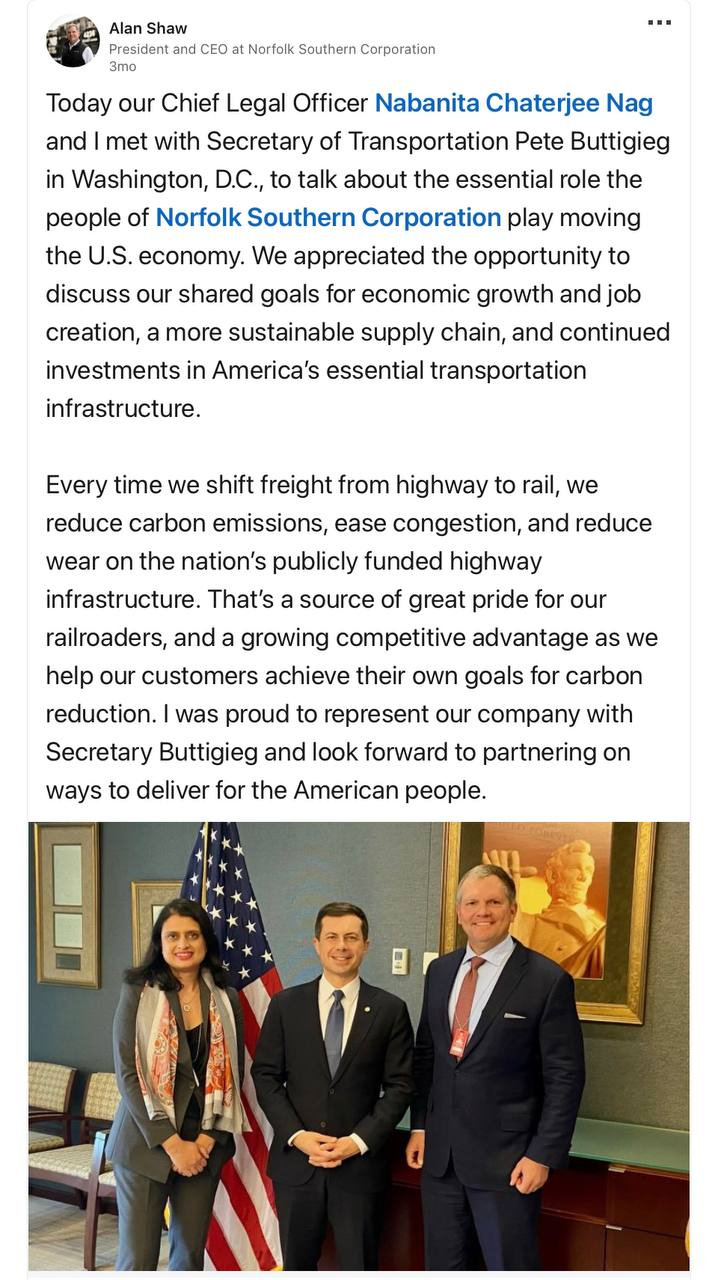

Shaw posted a picture of himself on LinkedIn posing with Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg in D.C. He touted freight as the green way to keep the supply chain rolling.

Every time we shift freight from highway to rail, we reduce carbon emissions, ease congestion, and reduce wear on the nation’s publicly funded highway infrastructure. That’s a source of great pride for our railroaders, and a growing competitive advantage as we help our customers achieve their own goals for carbon reduction. I was proud to represent our company with Secretary Buttigieg and look forward to partnering on ways to deliver for the American people.

It was posted just three months before the derailment in East Palestine.

Shaw wasn’t in Washington just to sing the praises of Mother Earth. A memo obtained by The Washington Post showed the trip “was an opportunity for Norfolk Southern to raise concerns about a proposed federal rule that would require trains, in most cases, to have two crew members. Federal regulators have argued that two workers could better respond to derailments and other emergencies, but the industry has pushed back against the proposal.” For Norfolk Southern, ESG provides a useful veneer for standard-issue corporate interests.

But Norfolk Southern alone is not to blame, and the incumbent administration has become another villain in this story.

As of this writing, President Joe Biden hasn’t visited East Palestine. When Biden opted to visit Ukraine instead, Conaway called it “the biggest slap in the face.” There the president announced an additional $500 million in aid to the Eastern European country.

Buttigieg only visited East Palestine after Trump stopped in town. Between the incident and Buttigieg’s belated venture to the town, the transportation czar had preoccupied himself with discussing the problem of white construction workers taking jobs in communities of color. By the time he traveled to East Palestine, it looked like little more than a face-saving act.

To be sure, Trump’s trip also bore a self-serving look. In the weeks and months prior, Trump had complained about Fox News ignoring him. Immediately after his trip to East Palestine, the former president bragged about the TV ratings it got him. He shared an internal “viewership report” on Truth Social, his social media network, and renewed his grievances about Fox News. The full report reads:

VIEWERSHIP REPORT

President Trump’s 2/22 visit to East Palestine, OH

TOTAL PEOPLE THAT SAW COVERAGE (SOCIAL+ TRADITIONAL): 178,052,414

TOTAL SOCIAL MEDIA USERS THAT SAW COVERAGE: 144,037,338

TOTAL TRADITIONAL VIEWERS THAT SAW

COVERAGE: 34,015,076This report searched for the term “East Palestine” + “Trump” what you will see is while traditional outlets like Fox News are woefully derelict in their reporting with what you did, the word is still getting out there in a big way. Specifically, when the announcement was made last week there was a bump of coverage reaching about 2 million on social channels and 10 million on other channels.

However, your numbers this Wednesday were off the charts with incredible reach, 144MM on social and 34MM in other channels. The visit meant a lot for the people of East Palestine and the surrounding communities. The trip gave them hope and raised the awareness needed to combat the incompetence of the Biden Administration. As you will see a sharp spike in the positive sentiments as well.

Wednesday, Feb 22, 2023

Social Media Reach

144 037 338

Non Social Reach

34 015 076

He continued complaining on Truth Social about Fox News not covering him as much as he would want in the days after the trip.

Trump may have seen the visit as a public relations victory for his 2024 campaign, but it also called attention to his own record.

Critical observers noted that Trump did not visit DuPont, Washington, when a train derailed there in December 2017, killing three and injuring 65. Moreover, an Associated Press review of Transportation Department policies found that during Trump’s first year in office:

at least a dozen safety rules that were under development or already adopted have been repealed, withdrawn, delayed or put on the back burner. In most cases, those rules are opposed by powerful industries. And the political appointees running the agencies that write the rules often come from the industries they regulate.

Indeed, Trump appointed Ron Batory as head of the Federal Railroad Administration. Batory was president of Conrail, a service provider for Norfolk Southern.

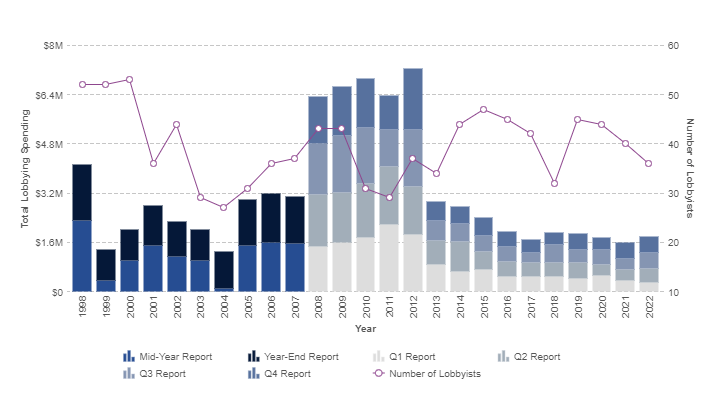

The truth is that the problems that make these sorts of incidents all too common are systemic. The rot, in other words, is bipartisan. Railroad companies lobby both Republicans and Democrats to block and undermine regulations that make railroads safer in the name of cost-cutting and efficiency.

In an interview with The Intercept, former presidential candidate Ralph Nader explained how deep the problem goes. “The federal railroad administration is the most captured regulatory agency in the U.S. government,” he said. “It is owned and staffed by the railroad industry. They have anesthetized it, and created the weakest regulations and standards imaginable. They are so weak, if they were any weaker the insurance industry wouldn’t cover railroads.”

A very similar derailment in New Jersey in 2012 that spilled 23,000 gallons of vinyl chloride set in motion the wheels of reform amid a streak of other incidents. Then-President Barack Obama attempted to implement more safety regulations on the railroads, specifically pertaining to hazardous materials. But pressure from the industry hampered those reform efforts and limited their scope. Data from Open Secrets show Norfolk Southern’s lobbying activity had increased around this time.

Under Trump, aggressive lobbying from railroad companies, mostly aimed at Republicans, managed actually undo certain safety provisions. “Specifically, regulators killed provisions requiring rail cars carrying hazardous flammable materials to be equipped with electronic braking systems to stop trains more quickly than conventional air brakes,” a report by The Lever noted. “Norfolk Southern had previously touted the new technology—known as Electronically Controlled Pneumatic (ECP) brakes—for its ‘potential to reduce train stopping distances by as much as 60 percent over conventional air brake systems.’”

“But the company’s lobby group nonetheless pressed for the rule’s repeal, telling regulators that it would ‘impose tremendous costs without providing offsetting safety benefits.’”

All that is not to say Trump’s policies directly caused the derailment in Ohio—even The Washington Post has refuted that claim. But it does show why the “man of the people” narrative he tried to weave with a photo shoot in East Palestine rings about as hollow as Obama’s “hope and change” shtick. The bottom line is that Norfolk Southern has successfully spent millions on lobbying red and blue politicians, and no one—not Obama, Trump, or Biden—has been immune from industry pressure that has resulted in outcomes that make the public less safe.

A look at the National Institute on Money in Politics database gives us a better picture of who is getting what from Norfolk Southern. The institute compiles campaign-donor and lobbyist information from government disclosure agencies nationwide.

An overview of its political contributions over the years shows that Norfolk Southern has given more to Republicans than Democrats—but Democrats get plenty, too.

DeWine himself has received thousands of dollars from Norfolk Southern and has been connected to the railroad company through Dan McCarthy, who was DeWine’s top lobbyist until he resigned amid a scandal in 2021.

In 2021, FirstEnergy agreed to pay a $230 million fine for bribing public officials in an effort to secure a $1 billion bailout for two nuclear plants in northern Ohio. FirstEnergy used a dark money group called Partners for Progress to that end, which it set up in 2017. At that time, McCarthy was president of Partners for Progress and a lobbyist for FirstEnergy.

According to his LinkedIn, McCarthy also led The Success Group, another lobbying firm, from 1994 to 2020, which overlapped with his tenure as DeWine’s legislative director. The Ohio Lobbying Activity Center database shows Norfolk Southern has employed the group to lobby on a wide array of railroad-related issues.

DeWine’s relationship with the railroad industry has also been scrutinized due to the marked difference between his approach to East Palestine versus his far more aggressive handling of the coronavirus pandemic. In 2020, DeWine fought his fellow Republicans over Senate Bill 311, which would have limited his health department’s powers to quarantine or isolate people. After DeWine vetoed the bill, Senate President Larry Obhof, a Republican, declined to override the governor.

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, McCarthy led DeWine’s efforts to fight restrictions on his health department’s powers.

In stark contrast, DeWine has refused to issue a disaster declaration that would bring more aid to East Palestine. Locals repeatedly noted to me what they consider a far more moderate approach to this environmental and health emergency. Moreover, how DeWine declared the coast clear in East Palestine didn’t help assuage these concerns.

On Feb. 15, the governor said in a press release that the “Ohio EPA is confident that the municipal water is safe to drink” after tests returned with “no detection of contaminants associated with the derailment.” But those tests were not conducted by state or local officials. Instead, they were done by AECOM, a Dallas-based consulting firm hired by Norfolk Southern. DeWine received at least one contribution from AECOM last year.

Alarms immediately began to sound about both the methodology of the tests and DeWine’s use of them. Sam Bickley, an aquatic ecologist at Virginia Scientist-Community Interface, told the Huffington Post that the findings were unreliable. “I find this extremely concerning because these results would NOT be used in most scientific applications because the samples were not preserved properly, and this is the same data they are now relying on to say that the drinking water is not contaminated,” he said. Nicole Karn, a professor in the chemistry department at Ohio State University, echoed Bickley’s concerns to the Cincinnati Inquirer and raised additional issues about methodology.

“More testing should be done,” Karn said. “And that’s sort of the main thing: We need to make sure samples are collected properly, so we have more faith in the results we’re seeing.”

When I visited East Palestine again on Feb. 28, Susan Reynolds told me I should return during happier times to get a real sense of the town. She owns a tanning salon near the site of the derailment, tucked into a plaza amid a crop of industrial buildings. She said Fourth of July festivities around here would tell a stranger all they need to know about East Palestine.

We chatted about customers who have reported symptoms they believe are connected to the incident and others who cannot return home due to health concerns.

Down the road from her salon, at the wreck site near East Taggart Street, crews of workers have resumed handling hazardous materials after a pause behind and around a blue industrial building beside the tracks.

The EPA set up an office in downtown East Palestine, where life has not yet returned to normal. Mascher said things aren’t easy for the flower shop these days, but they are making ends meet. “What happened here is still terrifying,” she said. As we talk, a worker wonders aloud if the rain has made it harder to get rid of the contaminants. Another approaches me to say she knows a man with three little boys who cannot return home.

As I leave the flower shop, a black Norfolk Southern train screams down the line.

There are reports three miles away in Negley of people smelling what they describe as paint thinner and experiencing headaches, keeping concern in the air. But this part of America is resilient and rooted.

As of this writing, at least 15 lawsuits have been filed in federal court, many against Norfolk Southern. Courtney Miller, who lives 100 yards from ground zero, and a group called We The Patriots have filed a lawsuit against the EPA and DeWine.

East Palestine’s motto is “Where You Want to Be.” This is their home, and it, like they, aren’t going anywhere.

Pedro,

Thank you for an incredible blow-by-blow account of another tragedy which will have long term consequences for the people of East Palestine, Ohio.

Heartbreaking and infuriating.