Ancient Greeks and Transhumanists

Or mystery cults and modern would-be Methuselahs.

The most important thing to know about Bryan Johnson is that his raison d'être is to live forever.

His slogan is “Don’t Die,” and he is spending a Sultan’s fortune on evading death’s grasp.

All aspects of his life are carefully measured and strictly routinized with the precision and predictability of a fine Swiss watch. Trying to cheat the Grim Reaper of his due forces you to live on a pretty dull and safe circuit.

But the clock continues to tick toward the hour of his arrival anyway. There’s no changing that, something the Greeks learned to cope with without resorting to imbibing the blood of their children, as Johnson did until he switched to the plasma exchange method. If it seems strange to rope old superstitions like the Eleusinian Mysteries around the topic of transhumanism, consider that much of what people like Johnson are into now would have been seen as ritual magic or sorcery in the past. Indeed, in my piece for Chronicles, I cited the third law of British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

The Mysteries (we’re getting there), enshrouded in a secrecy enlarged by the ages, were fundamentally about embracing our mortality. I am sure that, at some point, we will be able to develop a technological workaround to that inconvenience, like digitally storing our consciousness in a cloud or an implant that would allow us to swap the entirety of the human mind between bodies à la Altered Carbon.

Even if we could do that—and Elon Musk claims to have already done it—it still wouldn’t count as true immortality. Backing your brain up to a cloud is a parlor trick amid the infinite echoes of eternity.

More importantly, humans shouldn’t live “forever.” There is no doubt in my mind that the outcome would be identical to what life is like for the Meths in Altered Carbon. These are the ultra-wealthy set who have the means to prolong their lives for hundreds of years through cloning and cortical stacks—basically a thumb drive for your consciousness. They reside in literal castles in the sky and are named after Methuselah, the biblical figure mentioned in Genesis whose days were nine hundred sixty-nine years. Their unnaturally long lives have numbed them to all but the most extreme and depraved sensory experiences. It is only through rape, torture, and murder—often done all at once—that they can feel anything like pleasure anymore.

Peel back the opulence, and they are miserable sociopaths and, ironically, obsessed with avoiding “true death,” which no one can, not really. These are people who, despite their long-drawn lives, are cut off from the past in a sense. In attempting to transcend death, the human part of them withers and dies. They forget what our forebears knew about death and dying. At Eleusis, no one would forget.

The roots of the Mysteries are in the Bronze Age, with some speculation around Minoan Crete as the provenance. The associated rites and ceremonies represented the abduction of Persephone, the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, by Hades, who snatched her one day as she was gathering flowers in the Vale of Nysa. Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, searched relentlessly for Persephone. Her agony was such that it brought the seasons to a halt. Crops died. Drought starved the fields. All life was threatened with extinction.

In the end, Persephone and her mother were reunited, but as the result of a trick by Hades, she was only able to return to the world of living for certain months every year, which reflected the cycle of the seasons. There’s some debate, but generally speaking, spring and summer were associated with their reunion, while autumn and winter signified Demeter’s grief at the loss of her daughter.

On her quest, Demeter befriended the royal family of Eleusis, particularly Triptolemus, to whom she gifted the art of agriculture and who, according to Homer, became one of Demeter’s first priests and a first among men to learn the secrets of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Triptolemus is depicted as a young man, associating youth with innovation. Writing this, I thought of Luke Farritor, the 23-year-old engineer and Roman history fan who, as a college student, helped decode a nearly 2,000-year-old scroll recovered from the ruined city of Herculaneum. Farritor is now working at the Department of Government Efficiency, which, however you may feel about that agency, is an undeniably remarkable feat for someone his age.

If he ever gets a chance, maybe Farritor should visit Kerameikos, the Athenian cemetery where those who had been initiated into the Mysteries began the Eleusinian Procession, a long walk along the Sacred Way that started at dawn and ended at the Sanctuary of Eleusis at nightfall.

It mirrored Demeter’s experience. The beginning of the procession through the cemetery reflected her loss and despair.

The approximately 14-mile trek imitated the search for her daughter.

The ascent of Mount Aegaleus and descent that ended in Eleusis, followed by a feast and festivities, commemorated their reunion and what it symbolized.

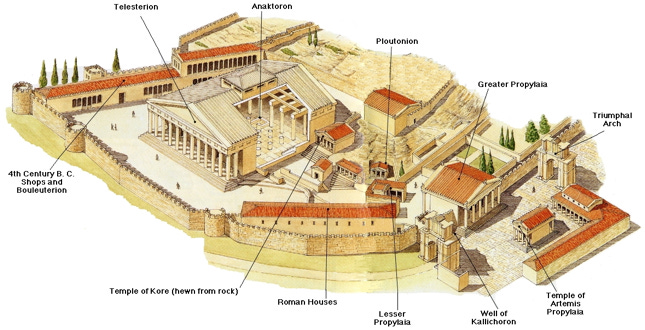

Initiates drank a wine called kykeon that induced visions and an intense state of ecstasy in those who partook. As the rites and procession progressed at Eleusis, they would arrive at the Plutoneion, a cave that formed the entrance to Hades. At a nearby well would women dance and whirl. According to Kalliope Papangeli, who has worked as the chief archeologist at the sanctuary, a priestess would emerge from the well, dramatically reenacting the myth. You can imagine how powerful an experience this would have been under torchlight.

Beyond the maw of Hades was the Telesterion, the great hall wherein the heart of the Mysteries awaited and which housed the Anaktoron, a small rectangular structure that contained sacred objects. The rites that occurred within these walls were kept secret under penalty of death, which is why we still don’t really know what went on in there, despite it being home to arguably the most famous and enduring religious ceremony of antiquity. All we know is that the highest mystery entailed “an ear of grain cut in silence” by a hierophant, which signified the eternal cycle of the seasons and new life. The whole ordeal gave participants the sense that they were standing on the veil between this world and the next. It also gave them hope for the promise of life after death and, therefore, removed its bitterness.

The Mysteries lived on, steadily declining, until 396 A.D. The Goths, led by Alaric I, sacked the sanctuary for good around that time. As paganism was eclipsed by Christianity, aspects of the Mysteries that had been associated with Demeter were transferred to Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki, a martyr who became a patron of agriculture. Christians also adopted words like “mysterion” to describe the mysteries through which God is revealed to man.

There’s another myth that comes to mind to tie this rambling piece off and back to transhumanism. It’s the story of Marpessa, a princess who was abducted by Apollo. She was just his type: beautiful and married.

According to Homer, her husband was a man named Idas, the “mightiest of men that were then upon the face of the earth.”

The mightiest, yes, but still just a man.

In one version of the myth, as the god and mortal fight over the maiden, Zeus intervenes and asks Marpessa to choose between the two. Let her decide, he says.

She goes with Idas.

She chooses the surety of death over the promise of endless felicity. Why? Because she knew that Apollo would tire of her, as that which cannot die tires of everything, and that she would end up unhappy and alone anyway. Perhaps she also knew that we are meant to endure sorrow as much as joy and that the finitude of our common fate is what makes it beautiful. As the English poet Stephen Phillips has her say:1

Yet I being human, human sorrow miss. That half of music, I have heard men say, Is to have grieved.

“To sorrow she was born. It is out of sadness that men have made this world beautiful,” wrote Charles Mill Gayley of the Marpessa myth. And so she made her choice. To live and die with Idas. Marpessa denied a god for mortal love, knowing all that it entailed:

When she had spoken, Idas with one cry Held her, and there was silence; while the god In anger disappeared. Then slowly they, He looking downward, and she gazing up Into the evening green wandered away.

I do not think there is a truer sentence in the English language than what Gayley wrote about Marpessa. Beauty is born out of sadness, out of a confrontation with that ultimate inevitability, the one thing denied to gods, reserved alone for man, the envy of angels. There is a line in the film Troy (2004) delivered by Achilles to Briseis that is too good not to use (even if it’s incongruous with the actual Homeric view of these things) here:

The gods envy us. They envy us because we’re mortal, because any moment might be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we’re doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again.

A long time ago, some people who wandered in the light and dark over the fertile plains and whispering streams of Attica carrying myrtle branches bound by bacchus rings and shouting and mourning and drinking and dancing and singing in commemoration of this one life had a better grasp of that than billionaires today.

From Marpessa by Stephen Phillips.

Pedro, thanks for the beautiful post. It reminds me, in some way, of the book Tous les hommes sont mortelles by Simone de Beauvoir. The quest to live forever.

I’m an Orthodox Christian and for me Jesus Christ is the only way to get there.