Sometimes less says more.

That was certainly true in Rutger Hauer’s case when he played Roy Batty in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which is based on Philip K. Dick’s novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968).

Harrison Ford stars as Rick Deckard, a jaded cop whose job it is to decommission Nexus-6 replicants. These are androids composed of organic material and virtually indistinguishable from humans, except for their enhanced speed, resilience, strength, intelligence, and complete lack of empathy. They are designed to serve humans and have a built-in lifespan of four years. After a series of violent uprisings, their existence on Earth is outlawed, giving rise to a specialized police force—Blade Runners—tasked with hunting down and forcibly “retiring” every last unit.

Batty is the leader of a rogue band of replicants on a very human mission: to buy more time from their creator, Eldon Tyrell. Although the film is a loose adaptation, it captures the essence of Dick’s novel, at the heart of which is the question of what it means to be human. And though Ford plays the main character, Hauer stole the show with a 42-word monologue. It’s delivered near the end of the film amid a confrontation between Batty and Deckard.

Deckard is slowly losing his grip, dangling from a skyscraper in the pouring rain as Batty looks down on him. His face curls into a smile as Deckard writhes, now less a man than a doomed worm on a hook. As the Blade Runner slips with a helpless gasp, Batty catches his arm and raises Deckard to safety. By this point, the audience has seen Batty crush a man’s skull with his hands as if it were nothing. The act of mercy is unexpected and seemingly out of character.

Batty only has moments left before he expires, and with a bewildered Deckard looking on, he says:

I’ve seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off (the) shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.

Writing about this scene doesn’t do it justice. It’s the rain. The music. Batty’s cadence and softening features. It is Ford’s countenance running from horrified confusion to an expression of solemnity and sorrow as the android speaks in poetry.

None of it would have been possible without Hauer, who was given a different and longer version of Batty’s last words, which he found loaded with “hi-tech speech.” Without notifying Scott, he chopped it up and added the line: “All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.”

Hauer’s delivery so floored the crew that they cried and applauded after filming it.

The scene is one of the most powerful in cinema because of how it juxtaposes Batty and Deckard, with Batty demonstrating not only mercy that Deckard would have denied him but grace, entrusting the hunter with a glimpse of a human soul in that final moment of sublimity. Batty fails to extend his life, but he dies as a man would. Choosing. Forgiving. Unafraid.

The whole thing is maybe a minute long, but those few timeless words would outlive both Batty and Hauer, who passed away in 2019.

I think that this is one of the main functions of fiction. To show us truths that are only intelligible through feeling. The stuff that resonates in our bones. It puts us in the position of Deckard. In awe of what reason says cannot be: a machine built to be a slave whose last act is an assertion of its individual sovereignty—of its soul. What, then, are we to make of those who would build such creatures and then destroy them? Fiction invites us to wonder.

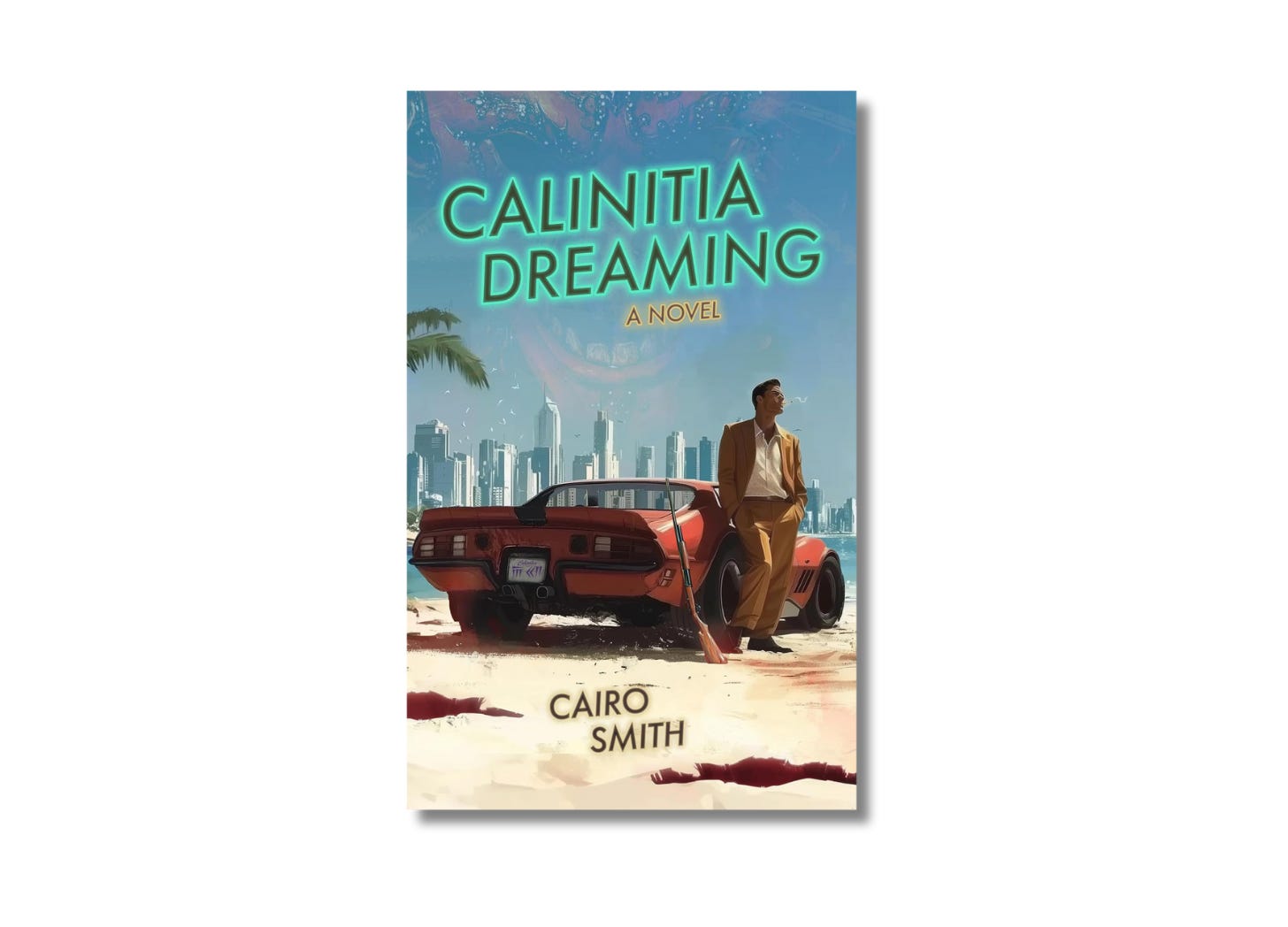

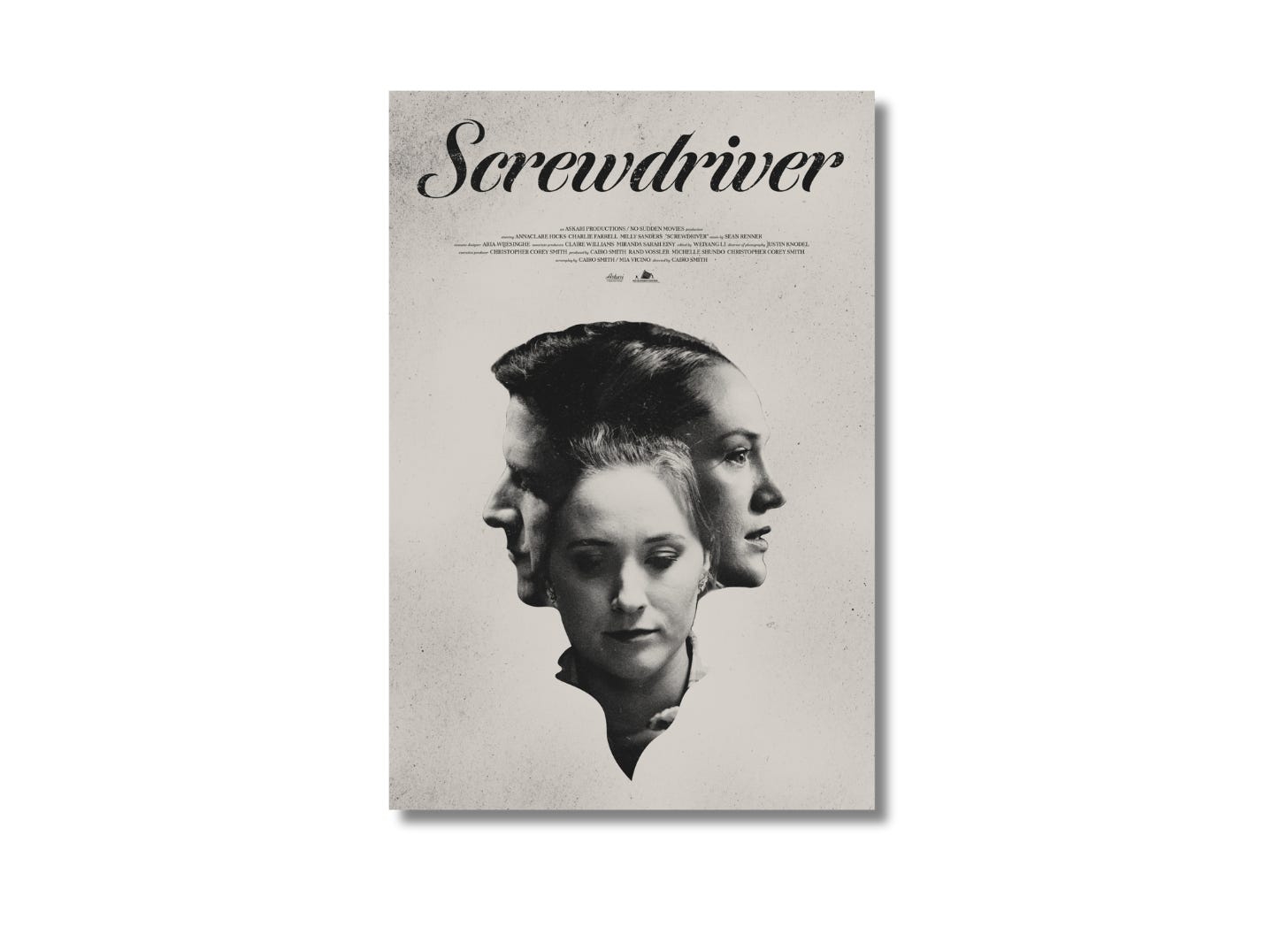

Cairo Smith knows a lot about wonder. He’s an award-winning writer and film producer who publishes Futurist Letters, where you can find articles on art, politics, literature, and more.

Cairo’s latest novel is Calinitia Dreaming, a sun-drenched neo-noir trip into a world of muscle cars and shadowy figures, richly and carefully constructed by the author. He also wrote and directed Screwdriver (2023), a psychological thriller produced by Askari Productions, his Los Angeles-based company.

I recently became a fan of Cairo’s work, and our conversation only confirmed my suspicions that he is an eminently gifted creative who approaches the craft with many of the same questions that PKD had about humanity, mortality, and the transcendent.

These things are very personal for Cairo. A few years ago, he was in a terrible accident that changed the course of his life. It’s a story he wrote about in an essay called “The Cure,” and one I asked him to tell during our talk. I was struck by his strength and optimism in the face of profound suffering, and I know that you will be, too, if you listen.

I hope you will enjoy our conversation and check out his books here. You can also follow him on Twitter here.