Humans have been telling stories about the world around them since the first man stoked the embers of the first fire that set the night ablaze and chased away the dark. Parmenides equated night and darkness with ignorance, and thus stories—narratives that provided some sense of order and resonance with lived experience—illuminated the lives of men who wove, memorized, and recited them, passing them down orally from one generation to the next like a torch.

The true salience of that lies in the fact that humans are, as far as we know, the only creatures endowed with the capacity for storytelling. Other animals can “talk” to one another, but that communication is limited for the most part to conveying the needs and wants of bare life. Only we have the capacity for reason, which is to say, only we have the capacity to think in abstract terms, which is the basis of logic and allows higher-order thinking in the pursuit of knowledge and mastery over nature. That faculty is why we are at the top of the food chain, but it is the same one that made us the first weavers of myths and epics; in other words, we applied our singular faculty of reason toward the creation of fiction. One might say that man did that in the past because he was ignorant, and continues the tradition today to keep himself entertained. But I believe that fiction is often more real than reality because the stories we tell are really studies of the human condition that cast experiences, familiar and unfamiliar, in vivid and accessible colors.

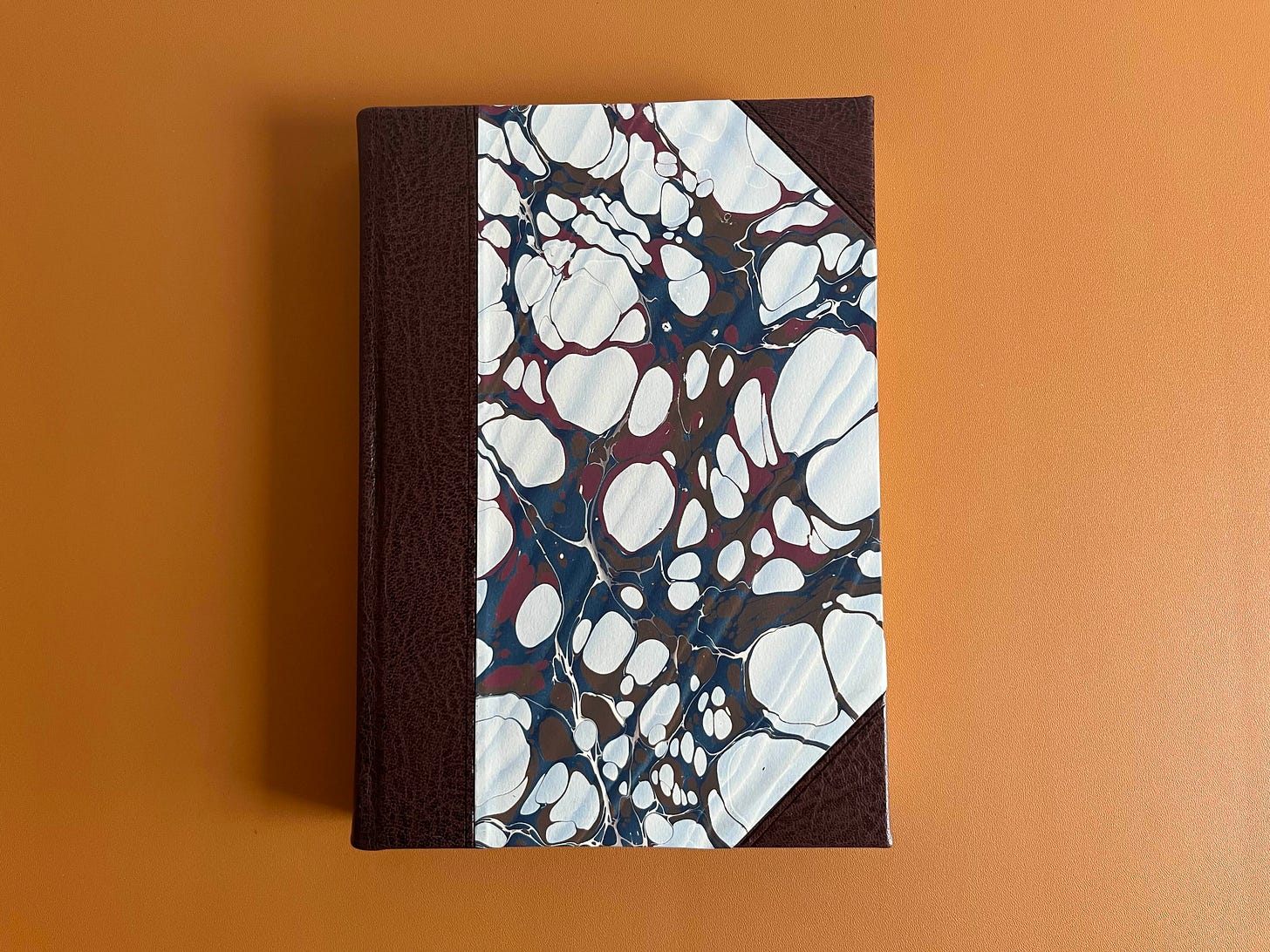

At some point, we decided to start committing these stories to physical memory, crystallizing them in murals, pottery, inscriptions, tablets, and scrolls. It was the Romans who developed the precursor of the book as we know it today, known to them as the codex, which consisted of bound parchment. The exact origins of the codex are somewhat mysterious, but the first written reference to codices comes to us from the Roman poet Martial, who encouraged his readers to leave those big, cumbersome scrolls at home and purchase his poems in what was then still a new and portable, chic format instead:

You who long for my little books to be with you everywhere and want to have companions for a long journey, buy these ones which parchment confines within small pages: give your scroll-cases to the great authors—one hand can hold me.

It is amusing and fitting that the earliest extant reference to the modern book was essentially a sales pitch.

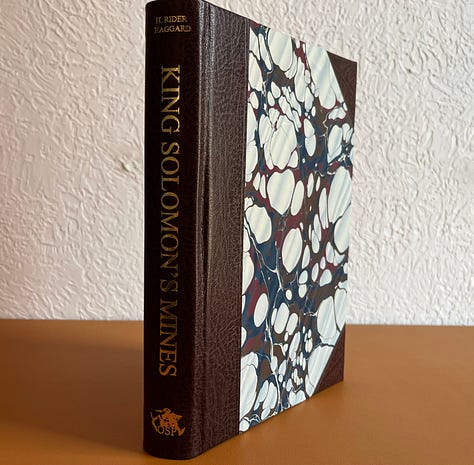

The art of bookmaking is fascinating because it arose from a need, a recognition that our narratives are worth preserving, worth taking with us wherever we go, worth passing down, even by the mute testimony of time when those who committed the words to memory have fallen silent and their recitation would otherwise be lost. But it is also an art that many seem to have forgotten. Not Old Sovereign Publishing, though.

Under George Carter’s leadership, Old Sovereign Publishing, a small, independent press, is producing gorgeous works of art in the classic style of bookmaking.

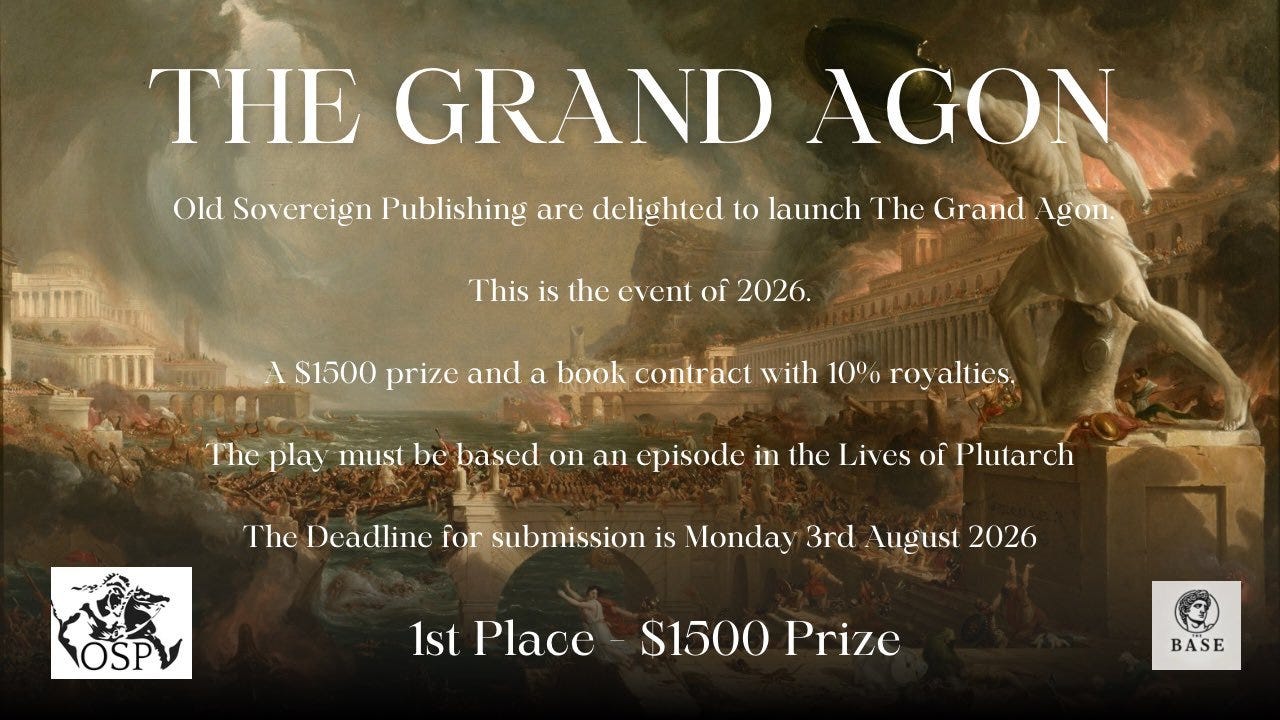

Carter commissions some of the best artists in the business to bring the pages of his catalogue to life with beautiful illustrations. He has also launched The Grand Agon, a playwright contest. The prize is $1,500 and a book contract. Two finalists will get to see their work performed on a London stage.

I wanted to know why George decided to undertake this enterprise. Publishing is hard, and I imagined that publishing meticulously crafted classics of literature was even harder, so it takes a special kind of person to decide to make this his cause.

Beyond that, I have been building a library filled with books that have been made to stand the test of time. I look at them like heirlooms, things that my children will someday read and inherit. When I had the opportunity to speak with someone in the business of creating the kinds of heirlooms I am seeking, I jumped at it.

I hope you will enjoy our conversation and consider checking out Old Sovereign Publishing’s offerings. You can also follow them on X at @OldSovPub.